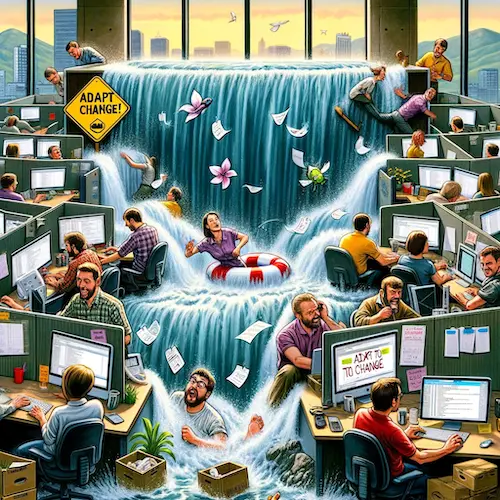

Fortnightly Waterfall (a.k.a Scrum)

Most modern software teams do some variation of Scrum. You can read the Scrum Guide here. According to many, Scrum is an “Agile” framework, but you could be forgiven for being confused by that, given the rigid structure that the guide prescribes. However, the Scrum Guide does give allowances for changing course and adjusting to meet goals. The ironic thing is that many teams ignore this and turn Scrum into Forthnightly Waterfall: two weeks of thrashing away at Jira tickets, regardless of whether they are adding value or bringing the team closer to their goals. Let’s explore.

The Waterfall Problem

In the 1970s and 80s, following an approach that resembled a waterfall was common. At the time, just compiling software was extremely slow, so a single mistake could cost a day or more.

Teams used to break the process down into sequential phases, and it was difficult for anyone in the team to work on processes in parallel. This approach has obvious problems, but it wasn’t as though people didn’t notice this. It was just the reality of computing at the time.

Enter Rapid Application Development (RAD).

Rapid application development was a response to plan-driven waterfall processes, developed in the 1970s and 1980s, such as the Structured Systems Analysis and Design Method (SSADM).

When I studied software development in the late 90s, RAD was already popular and well-understood. When we talk about “low code” tooling now, we are not talking about anything different from RAD tooling at the time. The idea was that we could prototype software quickly, put it in front of people, get feedback, and then adjust quickly before going live with the final version. There was nothing surprising about this approach.

What is Agile?

The “Agile Manifesto” is a meme website with a bunch of inane platitudes about making software that a bunch of dudes signed in 2001. I mean, literally 17 men, and not a lot of diversity there on any dimension. It encourages a flexible approach to building software instead of the rigid and more systematic approaches that had been popular at the time.

Agile probably had some positive impacts on the software industry. When I started in the software industry, it was still quite common for a project to take months to start just because upfront design and documentation would take months. Agile recommends getting working software early and collaboration. This is surely a good thing, but books had already been published on RAD when the Agile Manifesto was published, so I find it hard to swallow the idea that the Agile Manifesto was particularly revolutionary. We already knew the value of RAD, and Agile didn’t offer much over and above RAD.

Call me skeptical, but my opinion is that the Agile Manifesto was more of a revenue opportunity for writing books, speaking at conferences, and training material than anything else. The manifesto is not a blueprint for how to run a team or build software, and you can basically call any team structure “Agile”, but even the progenitors point to the eventuality of the

the Agile Industrial Complex and its habit of imposing process upon teams, raising the importance of technical excellence, and organizing our teams around products (rather than projects)

What is Scrum?

According to Wikipedia:

The use of the term scrum in software development came from a 1986 Harvard Business Review paper titled “The New New Product Development Game” by Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka. Based on case studies from manufacturing firms in the automotive, photocopier, and printer industries, the authors outlined a new approach to product development for increased speed and flexibility.

Schwaber and Sutherland, both signatories of the original manifesto, started doing what they called “Scrum” in the early 90s and integrated it into a formal framework. They finally published the Scrum Guide in 2010, and there have been several revisions.

In the early 1990s, Ken Schwaber used what would become Scrum at his company, Advanced Development Methods. Jeff Sutherland, John Scumniotales, and Jeff McKenna developed a similar approach at Easel Corporation, referring to the approach with the term scrum.[8] Sutherland and Schwaber later worked together to integrate their ideas into a single framework, formally known as Scrum.

What Constitutes an Agile Framework?

Well, I guess, an Agile framework would encourage the team to follow the Agile principles listed in the manifesto. Does Scrum do that?

Well, no. It’s a rigid, process-driven approach to building software. It defines roles, events, and artifacts that the team must adhere to in order to do “Scrum”. You don’t have to take my word for it. You can read it right here.

The Scrum framework, as outlined herein, is immutable. While implementing only parts of Scrum is possible, the result is not Scrum. Scrum exists only in its entirety and functions well as a container for other techniques, methodologies, and practices.

That’s the spirit with which the Scrum guide was written. Is that Agile?

Responding To Change

Whether or not Scrum is a good idea is a topic for another article, but I want to point out that Scrum Guide does allow for changes to the Sprint Backlog and Product Backlog during a sprint. The basic gist of Scrum is that the team picks a “Sprint Goal” (the why), and then the team works together to fulfill that goal for the duration of the sprint. A team should “adapt the sprint backlog as necessary”.

The purpose of the Daily Scrum is to inspect progress toward the Sprint Goal and adapt the Sprint Backlog as necessary, adjusting the upcoming planned work.

The guide repeats this here:

The Sprint Backlog is updated throughout the sprint as more is learned

That’s right there in the section about the Sprint Backlog, which is what most teams call “Sprint Board”.

So, the guide isn’t asking your team to work in a waterfall fashion, but how do most teams actually deal with this?

Fortnightly Waterfall

Teams often choose two weeks as the duration of sprints. I don’t know why that’s the de facto standard when the guide recommends up to one month, but the guide is clear about what you’re supposed to do every sprint. You’re supposed to

define a Sprint Goal that communicates why the Sprint is valuable to stakeholders. The Sprint Goal must be finalized prior to the end of Sprint Planning.

The Agile aspect is that your team is supposed to adapt to new information as the sprint progresses. You don’t doggedly chase the JIRA tickets just because you put them on the sprint board during the planning, but is this how most modern teams work?

No, actually. Based on my experience, most teams do something completely different. Sprint planning sessions usually involve:

- Dragging a dozen + tickets from the backlog - quite often with no relation to the sprint goal whatsoever

- Dropping them into the sprint board.

- Assigning them to individuals.

Team members work through the tickets individually and rarely circle back with each other to reaffirm the relation to the sprint goal. Once the Product Owner drags these tickets onto someone’s board, they stay there, and the expectation is that the developer finishes the tickets in the sprint. Often, there are so many tickets, and they are added in such quick succession that there is no time even to draw the connection between the JIRA ticket and the sprint goal.

Quite often, there is no tangible sprint goal anyway, but I’ve been in cases where the items on the board are no longer relevant to the sprint goal. In those cases, the Scrum Guide would dictate changing the items. It distinctly says, “although the Sprint Goal is a commitment by the Developers, it provides flexibility in terms of the exact work needed to achieve it.”

So why do the Product Owner and other people in the team get upset when you mention changing the sprint board during a sprint?

This isn’t something I’ve figured out. There is a strong expectation that the team needs to stick to the planning before the start of the sprint. I have experienced this in many teams, from small to large. I have mostly worked in Australian teams, but I’ve also experienced in teams outside Australia. I call this fortnightly waterfall: choosing a bunch of tickets at the start of the sprint and then sticking to them whether they are necessary for the sprint goal or not.

My personal frustration stems from firstly not really having a tangible goal in the first place, and then secondly, wasting time on working through tickets that add no value. Some Product Owners will discuss the possibility of removing a ticket, but it’s rarely a straightforward process, and it’s not only the Product Owner that puts obstacles in the way. People like knowing what they’re going to work on for two weeks, and some people get really upset when that changes.

However, surely, if Scrum has value, it’s in working towards a sprint goal as a team. What is the point of Scrum if the team gets bogged down in the same problem that older teams had, where the team grinds away on work that is no longer necessary or just plain wrong?

Wrap-Up

To be completely honest, I’m starting to wonder if modern software teams can salvage Scrum. I haven’t worked in any teams that follow the actual guide. Many of the things that Scrum teams do are not Scrum. As Ron Jeffries, an Agile Manifesto signatory, says “too often, at least in software, Scrum seems to oppress people”.

But, if it’s going to be any use at all, it needs to be about responding to change and working together as a team. Consider trying other approaches in your team or watering down the rigidity of Scrum. There are plenty of Scrum teams in the software industry. Not every team has to chase Scrum like an ideal. But, if you’re going to do it, get back to basics and place higher importance on the Sprint Goal, and adapting to changing conditions throughout the sprint.

I can say for sure that there’s an appetite for changing the way we do software:

In all seriousness, are there any jobs left where you just build the software in peace?

— Christian Findlay (@CFDevelop) February 3, 2024